Dear Reader,

Worlds end all the time. From moss being scraped off carelessly ending a tardigrade’s universe, to a supernova exploding and burning through a whole star system. World endings are equal parts stunning and terrifying—even if they are millions of light years away. So, of course they’ve been a fundamental part of the stories of every culture and religion. Our short fiction competition, Stories at the End of the World, to commemorate our fourth anniversary, draws its theme from one of the most enduring apocalyptic stories in the last two millennia: The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

While apocalypses seem, by their very seriousness, like they should be rare events, even in Christian mythos the world has ended a few times over starting with Adam and Eve being thrown out of Eden, and the last time being the Great Flood—a watery end that has echoes across various societies’ imaginations of the world. Apocalyptic endings of various kinds feature heavily in most religions’ founding myths.

There have been five major extinction events, rendering 98 percent of all life forms that existed extinct, most before modern humans even evolved. Hard as it may be to envision, all the world may be a stage, but we are not the only players. In the tapestry of life, we are but one strand. At the same time, in the period that we have dominated the planet, we have been the major harbingers of the end—for other humans, other species and ecosystems. We’re living through the Holocene, the sixth major extinction event, and this one is led by humans as we wipe out entire branches from the tree of life. Perhaps these cataclysms will become motifs in the religions of the future, like storms and floods are today.

Whether or not the apocalypse really arrives, our anticipation of it is constant, though it may take different forms—a nuclear holocaust for children during the Cold War in the 1980s, Y2K, the uproar around the Mayan calendar that ended in 2012, or climate change for those of us who watched Al Gore’s Inconvenient Truth (2006) in school. And it’s not just in stories about what could come—there is something about endings that fascinates us endlessly, even if it is not our own: will there ever be enough stories, recreations, or films of how the dinosaurs went extinct or what failings of past civilisations led to their end? Perhaps this is because the past is prologue, but also a warning and a map of what we might want to avoid or change. And stories are the way that we remember and protect ourselves.

But for many people, it’s not anticipation, it’s history repeating itself. In much of Asia, Africa, and the Americas, worlds ended centuries ago when dozens of kingdoms and empires were colonised and decimated by white Europeans. Worlds ended when Europeans spent centuries kidnapping and enslaving people, shipping them across the oceans. Whole populations were wiped out, and many more cultures erased and lost. But somehow, these worlds have lived on, adapting to these catastrophic shifts. The retelling and reclamation of these histories, which have often been erased or rewritten by revisionists, is a crucial tool to process this past, make sense of the present, and shape or anticipate the future.

The most recent world ending event, of course, was the COVID-19 pandemic. Few people were able to stay removed from the loss, fear and devastation. Whether you were gathering resources to keep your family fed and safe during this time, spending relentless hours every day on helplines, organising food and medical assistance, or just trying to follow the ever shifting instructions, distancing and holding on to whatever you could, everything shifted. As with every crisis, the most vulnerable—migrant workers, women, queer people, children, the already impoverished—were hit the hardest. And here we are, five years later, alive, changed, making many of the same mistakes and some new ones. This pandemic left millions displaced and impoverished, and these families may never recover. Long COVID has affected our health and left scars on our bodies in ways that may take decades to identify. Cultures of offices, schools, universities and other institutions have morphed and are still finding the new ‘normal’. The loss, its scale, and the scars it’s left, the fear of touch and breath itself, will echo through the years. Our societies have shifted in ways that we will only fully recognise as the children of this pandemic grow up and shape the world. Already books are being written about this terrible time, new apocalyptic stories entering into the halls of history.

Perhaps the reason for the ubiquity of apocalyptic imaginations is that endings are inevitable. As the arrow of time moves forward unrelentingly towards entropy, more worlds will be unsettled. And because, from the Bengal famine to the possible wiping out of the Shompen, so many ends are designed by people. But these are not individual actions or designs. And no single person, or even small collectives, can counter them effectively. These crises are when the governments, institutions and societies that we build are truly tested: we see exactly how kind, how paranoid, how selfish, how generous, and just how exhausted and fragile each person and institution is. But individual actions matter too. During the COVID pandemic, if you managed to keep one child fed, or just yourself, if you made art that brought comfort to someone, if you nursed a loved one back to health, if you made time to talk to one friend who needed it, you saved a small world; you started a ripple of what you would like the world to be. You became part of a story that will echo through history, entering the bones of those who lived through it, and will be passed from generation to generation.

Apocalypses take time. The pandemic lasted years. During the first extinction event, the first and second waves were a million years apart. Even if an atomic bomb is dropped or a virus mutates, nothing ends in an instant. An apocalypse ripples out through time and space. So, what we do in the post-apocalyptic world is just as important as what we do before it. Our actions continue to carry weight, perhaps even more so than before. So, what do we do when the apocalypse, big or small, comes? Who do we care for? What do we hold on to? How do you think a world might end? We invite you to explore these ideas more deeply, and share your stories with us, to add your voice to the tales of memory-keeping, caution or reimagining. You can send in your submissions for our short fiction contest, Stories at the End of the World, until May 17th.

Till Next Time,

Team Dark ‘n’ Light

Down the Rabbit Hole

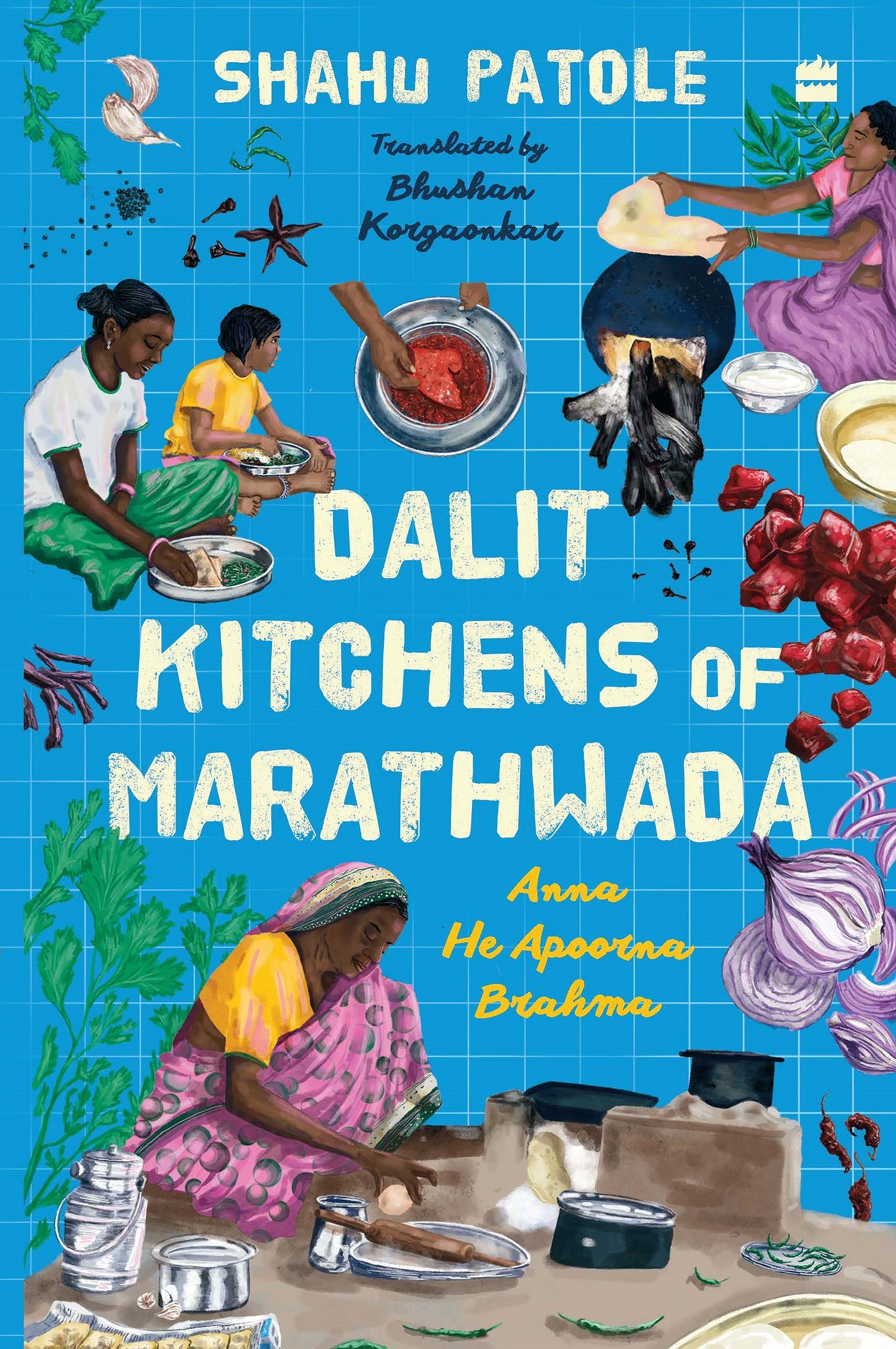

A Seat at the Table: An Excerpt from Dalit Kitchens of Marathwada

In this excerpt from Dalit Kitchens of Marathwada, Shahu Patole’s 2015 Marathi book translated by Bhushan Korgaonkar, we catch a glimpse of the rich language, history and recipes from the often stigmatised kitchens of the Mahars and Mangs of Maharashtra.

The moon in her many phases and faces is a companion, omen, comfort, myth and legend. In this essay, accompanied by her own artwork, author Sharanya Manivannan writes about her love affair with this heavenly body, and how it has shaped her over the years.

Editors Picks

Here are some works that explore apocalypses:

The Parable of the Sower (1993): This seminal work by Octavia Butler follows Lauren Olamina in a post-apocalyptic world affected by climate change and social inequality.

Worlds Ending. Ending Worlds (2024): An open access collection of essays, available here, published by The Käte Hamburger Centre for Apocalyptic and Post-Apocalyptic Studies (CAPAS) at Heidelberg University that brings together various thoughts and perspectives about the apocalypse.

Pack Your Go Bag: adrienne maree brown and Autumn Brown draw inspiration from Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower in this episode of the podcast The Best Advice Show and discuss practical steps to prepare for an emergency.

Tactical Hope: So and Pinar of Queer Nature share their learnings and wisdom on survival, the need to dismantle colonial notions of nature and the more-than-human and instead see it, and each other, as comrades and partners on the How to Survive the End of the World podcast.